A Prayer for Mecca

A Prayer for Mecca

“You will see the barefooted, scantily-clothed, destitute shepherds competing in the construction of tall buildings.”

The Prophet Muhammad (PBUH)

In response to being asked about the end times – Hadith Jibril

A Prayer for Mecca A real city

Like few other cities on earth, Mecca seems to buckle under the weight of its own dramatic symbolism. Mecca is rarely seen as a living city with its own inhabitants and historical development. Instead, it is almost exclusively seen as a site of pilgrimage, as a timeless, emblematic city. Mecca is a source, shaped by its own narrative which can be traced back to the time of Abraham. At the same time, increasingly significant effects emanate from it as the global Muslim population (the ummah or community) grows and becomes more connected. Amid a rapidly changing economic landscape, Mecca is re-examining its situation to itself and to the world beyond.

A Prayer for Mecca - Three Perspectives

Three Perspectives

A Prayer for Mecca - Three Perspectives

From Dream to Reality 2013 Desert of Pharan 2008–2015

01.

From Dream to Reality

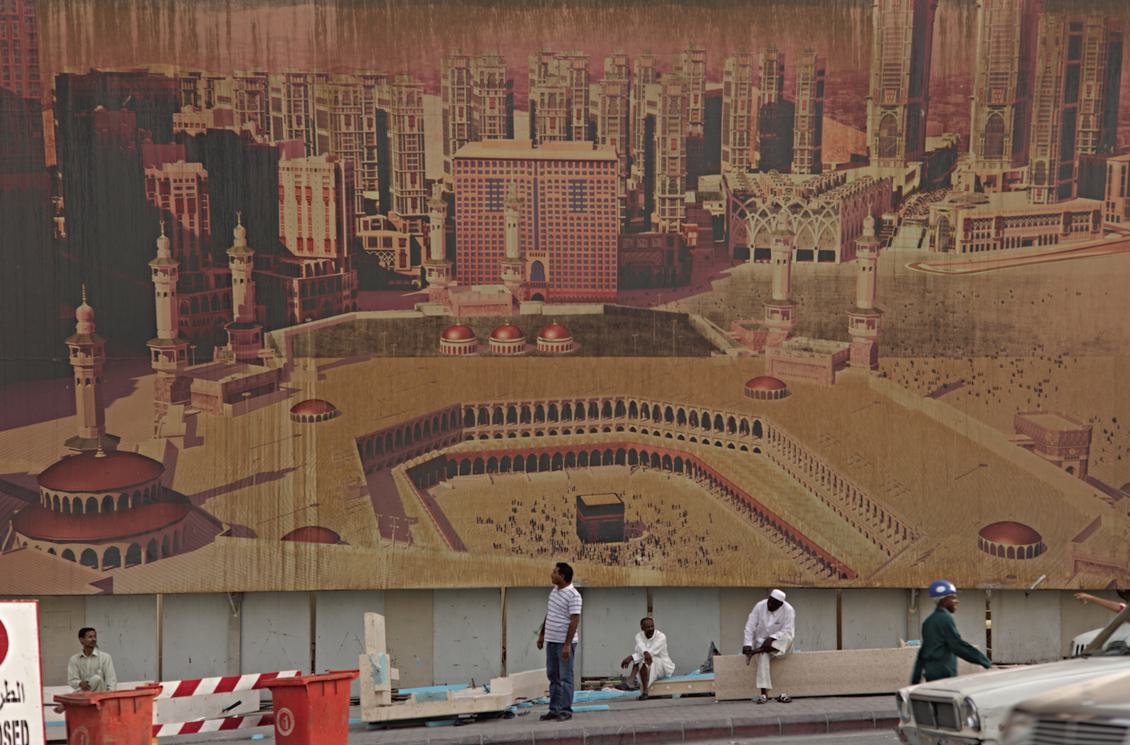

The redevelopments of recent years have exacerbated the tension between the living and the imagined. The denial of the real city is a denial of typical urban inconveniences like traffic, lack of public space, and the challenges of infrastructure. In this feat of signification, those who preside over the developments are freed from the burden of practicalities. In this conceptual space, they dream wildly, implementing plans for massive, unfathomable transformation. This grand vision is plotted in architectural models and impossible renderings, then proclaimed from giant billboards, in whose shadows the unacknowledged life of the place continues to be played out.

Desert of Pharan 2008–2015

Foundation for the New Tower 2015 C-print, 48 x 72 in (122 x 182.9 cm)

02.

Between Demolition and Construction

The speed and breadth of transformation introduces dependent concerns regarding the city’s social mechanics, the tense relationship between demolition and construction. Above all, it has concentrated the imaginative energy of Mecca’s inhabitants on what will remain once the work is complete. The landscape of the holy city teems with skyscrapers, with the current expansions immense, their ambitions signaled by the frenetic movements of cranes and bulldozers. The cityscape evolves perpetually – even the Kaaba is encroached upon, jostled among buildings that vie for space as the Clock Tower with its colossal crescent moon ascends. Elsewhere, life is lived between the ruins of a lost city and the crisis of consumerism and signification.

Desert of Pharan 2008–2015

Desert of Pharan 2008–2015

03.

The Worker and The Warning

A lone figure, hoisted skywards. This is the crescent moon that will crown the clock tower. In Ahmed’s story, Jabril “sits between reality and the impossible cityscapes of the future.” The worker’s mundane task becomes spectacle, as he glides through the air “like an angel bringing a warning.”

Leaves Fall in All Seasons, 2013

Jibreel (Gabriel), 2012

These are three competing, incompatible scenes – some of the many images, many lives and many perspectives that accumulate in Ahmed Mater’s ranging Mecca projects. Archives of found objects, relentless documentation in photography and film, restless wanderings that try to reconcile a place caught between the past and the future. These vistas unearth the unofficial histories eclipsed by wildly master planned and hastily assembled futures. They are images that unsettle and expand the expected idea of the city as a place of solemnity and prayer. These are works that interrogate the cohesiveness of place and time; as Mater wrestles with tradition, modernity and a warp-speed urban futurism, geographic and historical specificity becomes unmoored.

A Prayer for Mecca - Roads to Mecca

Roads to Mecca

His preoccupation with Mecca has prompted many observations of the place, encountering all the nested concerns of urbanism, faith, culture, history and social struggle have and producing wildly different works – their difference testament to the distinctiveness of the city. These are projects of travel and trajectories, different approaches that Mater characterises as “roads” – an appropriate analogy for the destinations of pilgrims:

“

As a prismatic city of many layers and configurations, Mecca is a place of physical and symbolic approaches. As it shifts and changes, the points of conceptual and geographical entry also alter. There is not one route to Mecca, but many roads: the road from Jeddah to Mecca taken by the many who perform Umrah and Hajj; the roads connecting the present to the past that are fast being lost under the rubble of deconstruction and construction; the roads hastily paved to ambitiously dreamt futures.”

A Prayer for Mecca - The only constant

Still from Road to Mecca I, 2017

The only constant

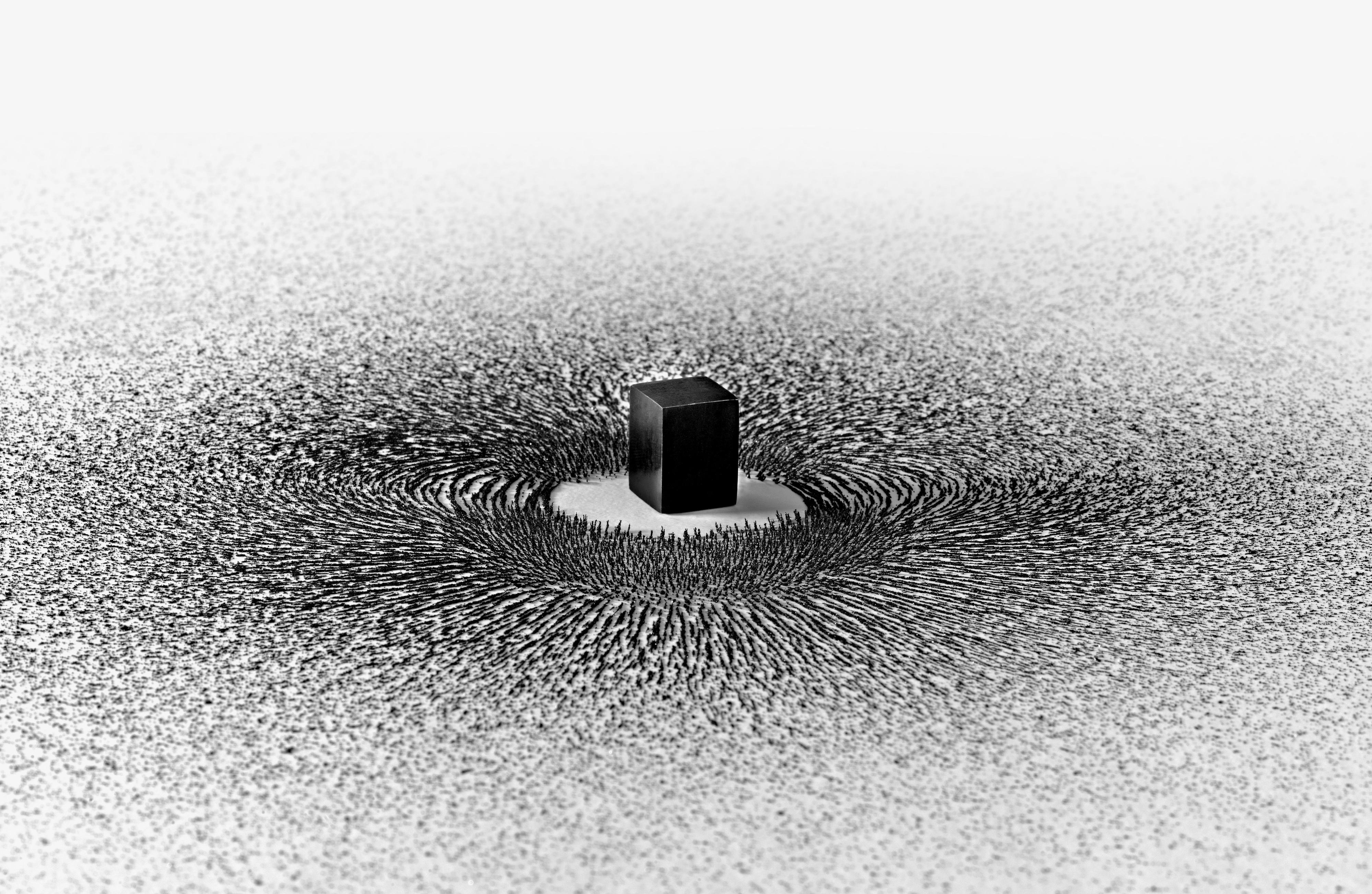

Through the lens of Desert of Pharan (2008–2015), a living city of unrest and change is captured – all shifting crowds and ascending construction. This change is tracked through history, found radiating from the artefacts and narratives of 100 Found Objects (2014). In contrast to the profusion of vying timelines and unofficial histories, Magnetism’s (2012) suspended monochromatic microcosm diagrams the immutable pull of faith that orders conceptions of the symbolic city.

Ka'aba, 2015

From Desert of Pharan

Magnetism, 2012, installation view during 'Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam' at the British Museum, 2012

“

“In Mecca, difference becomes the only constant. Today is different from yesterday and, by tomorrow, it will have altered again. There are seismic changes that stagger even the casual observer – the massive development of the Haram Al-Sharif being the most iconic. It’s a place loaded with historical significance, yet there isn’t any infrastructure left there that is more than 100 years old. It amazes me that for so many around the world today, especially non-Muslims who do not know the significance of the city, Mecca has become synonymous with impossibly tall buildings, the looming clock tower and the teeming cranes. What happens to the symbolic identity when the physicality is altered beyond recognition? The ‘difference’ between the potent invested symbolism of the place and the complete physical transformation is the most charged – how can it be so historically, religiously, symbolically robust while also being physically obliterated and changed beyond recognition?”

From Desert of Pharan

From Desert of Pharan

As the sketched outline of a new city is overlaid onto the demolished infrastructure of the past, the older city is eradicated. The city is recast, dominated by a more technologically advanced, materialist, consumer-driven understanding of urban space. What is not yet clear is the impact this will have on the emotional and psychological well-being of the inhabitants of the physical and symbolic city.

A Prayer for Mecca - Viewfinders

Viewfinders

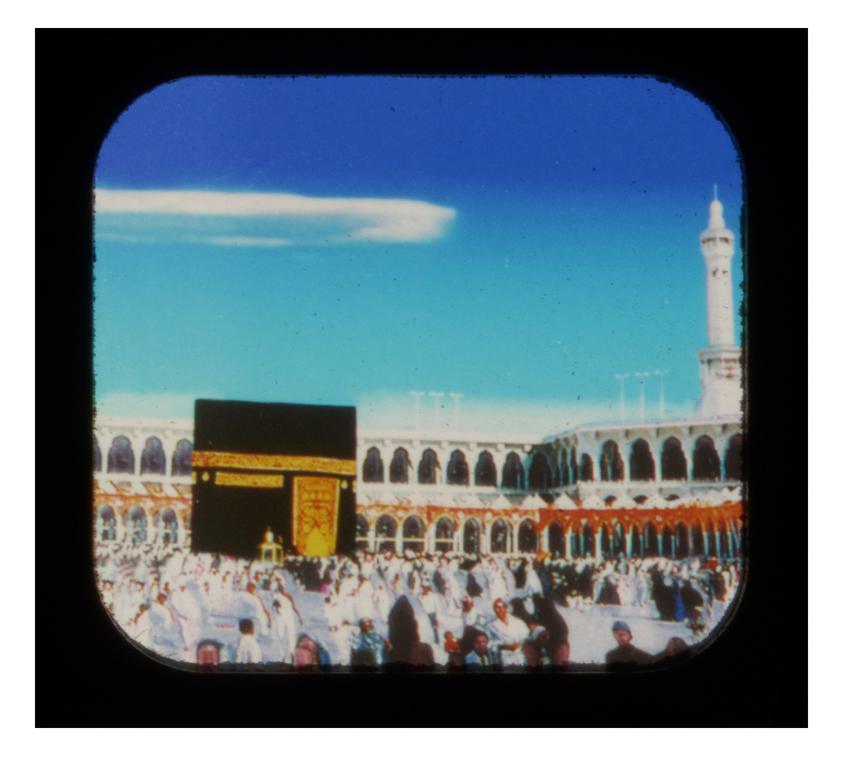

The first Desert of Pharan photograph was taken in 2008, but the project began long before, when Ahmed’s father bought back a Viewmaster stereoscope from Mecca to their home in the mountains of Aseer. These toys were ubiquitous across the Muslim world, emissaries from the holy city.

View Master Stereoscope, 1960–1980 CE

Found in an old shop in Mahbas Al Jinn, Makkah, now demolished.

From 100 Found Objects, 2014

Viewmaster Stereoscope 3D, 2000–2020 CE

Found 2013 in Makkah

From 100 Found Objects, 2014

“

There was something about those multi-perspectives on the city, the brief camera caught flashes of a place that ignited my imagination. The place I returned to was not the place that I’d remembered from childhood – a place that I’d constructed from my own memories, the stories of my family and the glimpses seen clicking through the Viewmaster’s wheel.”

Like these brief snapshots, the project is a documentation of moments, but it depends on multiplicity. Perspectives of the past, present and future unearth divergent, sometimes competing, vantages on a city that refuses to settle.

View Master Stereoscope, 1960–1980 CE

Found in an old shop in Mahbas Al Jinn, Makkah, now demolished.

From 100 Found Objects, 2014

Viewmaster Stereoscope 3D, 2000–2020 CE

Found 2013 in Makkah

From 100 Found Objects, 2014

A Prayer for Mecca - Surveillance

Surveillance

From that earliest viewfinder, held by a young boy dreaming of a faraway place, to other kinds of future technology, granting different vantages and perspectives on the city. Ahmed flew with military helicopters surveilling illegal entries into the city

Disarm Surveil, 2013

Disarm, 2013

A Prayer for Mecca - Windows to the past

Windows to the Past

He rescued windows, patchworks of brightly-coloured glass, from dilapidated buildings before their demolitions. Each pane a kind of material portal into a past that is being eradicated.

Mecca Windows, 2013–ongoing

From 100 Found Objects

Mecca Windows, 2013–ongoing

From 100 Found Objects

Mecca Windows, 2013–ongoing

From 100 Found Objects

A Prayer for Mecca - Live stream

Live Stream

And he encountered the new generation of ‘viewmasters’ – phone screens that document and track every moment of the pilgrimage, streamed across Instagram, Twitter and Snapchat.

A Prayer for Mecca - Commercial City

Commercial City

In Saudi Arabia today, contemporary models of urban development based on imported developmental know-how have become the starting point for a host of proposed new cities. For the most part, each will be constructed on a social and historical tabula rasa. Mecca presents an alternative dialogue between plan and reality. Like few other 21st century cities, it is rooted in a complex and highly emotive context in terms of its historical, geopolitical and religious symbolism. It is both one of the most visited places on earth and one of the most exclusive. Yet it is in flux, it moves, grows and invents itself again.

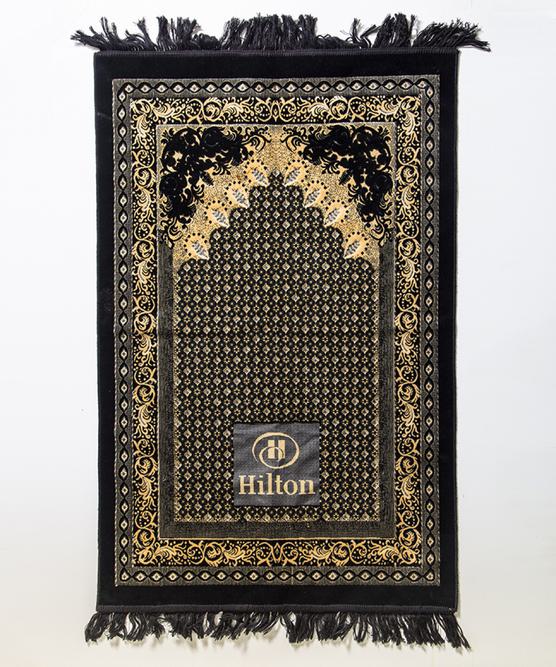

From 100 Found Objects, 2014

From 100 Found Objects, 2014

In between the mega-developments, the public space is squeezed, and the surroundings of Islam’s most important mosque privatised. As public space disappears under pressure of real estate speculation, security measures, and collective neglect, the price of private access to it increases. Mecca faces an unprecedented, yet abundantly practical problem – where to accommodate the massive, ever-growing transient population of hajj pilgrims? The problem of touristic infrastructure seems curious in this most spiritual of sites as hotel construction makes vain efforts to keep pace with the impossible capacity demands.

From Desert of Pharan

There are now more than 100 hotels, many built right around the Kaaba. These are the most luxurious, the rates reflecting their proximity, lavish facilities and finishings. Here, rooms will cost up to $3,000 a night. There are few who can afford or justify such expense, the division it imposes an anathema within the context of those dignified, fundamental levelling principles that are the very basis of hajj. Within this current manifestation of Mecca, the pilgrimage becomes fraught with contrast and contradiction. The precious core tenets of Islam, eloquently articulated by its customs and rituals, protected since the days of the Prophet, were never meant to compete with super luxurious hotels, Rolex, Starbucks (the logo altered, the woman it shows on every high street in every city of the world is removed here) and Burger King.

From 100 Found Objects, 2014

From 100 Found Objects, 2014

From Desert of Pharan

Room with a View, 2013

A Prayer for Mecca - Ritual City

A Prayer for Mecca - Ritual City

Ritual City

Entry to the sacred city is exclusively granted to the followers of Islam. The pilgrimage remains the central structuring principle – both symbolically and physically – of all that is Mecca. The rituals of the pilgrimage have been fiercely protected, and devotedly and consistently observed for fifteen centuries.

Magnetism, 2012

In the Grand Mosque, we begin with tawaf, circling the Kaaba seven times. The tight procession propels you; you are carried by the crowd. It is a fortunate pilgrim who manages to break free from this lulling press of people to kiss the Black Stone – the cornerstone of Islamic faith. This individual darting act is not a requirement, though the opportunity for essential physical connection is nevertheless an aspiration for many.

The Black Stone, 2014

Walkway to Mina, 2012

“

We pilgrims ultimately proceed out into the desert, first to the town of Mina, about five miles away, and then onward to the Plain of Arafat, ten miles farther east. At Arafat, I feel most closely the collapsing of past and present, a sense of immutable and unchanging history strung together year on year, century piled on century, as the ritual becomes a kind of sacrosanct object, a fixed point in the story of this city.”

Mountain of Light, 2015

Returning toward Mina, the pilgrims stop to throw small stones at three massive walls, an act symbolically recalling the three occasions when Abraham threw stones at Satan, who tempted him to disobey God’s command to sacrifice his son. Again, order trumps tradition here, with massive walkways recently constructed to allow safe passage for the masses.

Throwing Stones at the Devil, 2012

A final procession around the Kaaba concludes the hajj. Upon its completion, elation reaches fever pitch, overcoming the strict white order of the pop-up tent city of Mina constructed for hajj pilgrims. It becomes a place dedicated to wild and triumphant celebration, infused with a freeform euphoria: it resides here in the makeshift camp, emanates from each individual, but utterly transcends the place, the moment, and the self.

From Desert of Pharan

A Prayer for Mecca - A Prayer for a Real City

A Prayer for a Real City

Artificial Light, 2011

Mass, and more specifically scale, are important to the project. Most obviously, the swarming mass of pilgrims that come each year, like a wave, to the city – but also the scale of the individual human body in relation to the urban – and how this speaks of the scale of one life among the multitude of lives, stories, and unofficial histories. There are interior scenes and aerial shots, images of vast echoing construction sites and crowds thronging holy sites. More than being merely read as a commentary on Islam, or religious experience, the ranging ideas prompted by Desert of Pharan and the subsequent derives of 100 Found Objects, engage with a global dialogue about urban development: pristine symbolic cities vs. their more knotty and complex lived realities; tensions between private and public space; the individual vs. the multitude.

There is violence in the pace of change but elation in the immutable pull of this holiest site. The fraught destruction and revival of the city means its identity is constantly fractured, pulled apart and, from this rubble, something else made. What is made is unstable, with only tenuous historic foundations – yet it is also reaching ever skywards. The obliteration of history is particularly brutal – it happens very literally as old buildings are pulled down and archives are lost.

“

“Photographing the city, in some part, stemmed from a fascination with resolving the timeless, symbolic, nostalgic, remembered city with its physical counterpart – the layers shifted and revealed even more layers. The more I looked, the more Mecca appeared to me like a microcosm of many universal concerns – private development encroaching on public spaces, the fortunes of migrant communities, the tension between urban planning and religion…”

Stand in the Pathway and See, 2012

In this way, the action of these projects have resolved into a prayer for both the real and the symbolic city, the past, the present and the future. A monumental documentation of flux, Mater tries to fix fleeting moments, and track the threads of disappearing histories, before they are obscured forever beneath the rubble.